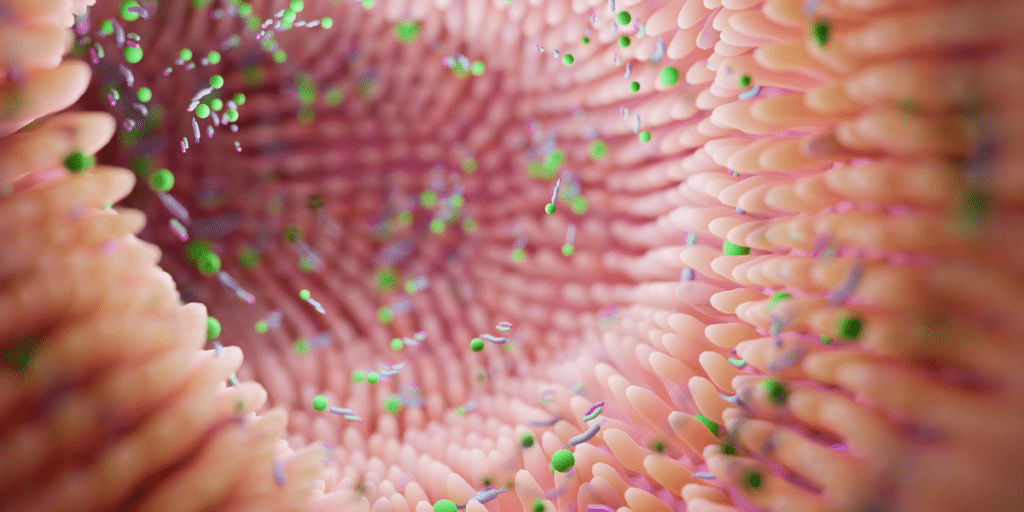

Thirty years ago, if I told you that the bacteria in your body were partially responsible for the health and proper function of nearly every organ system, I’d probably have been laughed out of the room. However, research into the microbiome and dysbiosis has skyrocketed since that time, and the microbiome is well established to be either a source of health or a source of potential inflammation and systemic dysfunction.

The health of the gut microbiome is imperative for the overall health of an individual. Dysbiosis has been implicated in several diseases, from metabolic disease (insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, etc.) to autoimmune diseases, depression, and other mental health and cognitive disorders.

This post is going to dive into the basics of gut dysbiosis, which is defined as opportunistic (bad) bacteria overgrowth with decreased levels of commensal (good) bacteria.

This is the third post in our gut health series. To get a deeper understanding of gut health, check out my posts on signs of good digestion and leaky gut.

Table of Contents

Dysbiosis: What Is It and What Can You Do About It?

If you or your clients are dealing with gut health issues, you’ll want to familiarize yourself with the topic of dysbiosis. In this blog post, I cover several topics, which include:

- Framing the microbiome

- What is dysbiosis

- Health effects of dysbiosis

- Potential causes of dysbiosis

- Potential solutions for dysbiosis

Keep reading to learn more about how gut bacteria impact overall health and contribute to a healthy immune system.

What is the Microbiome?

Many coaches and individuals reading this may know the importance of the gut and its microbes by now. Gut health has become significantly more mainstream within the past 3–4 years, so more people are talking about things like dysbiosis, gut bacteria, gut flora, and gut microbiomes.

You’ve probably heard of the gut-brain axis in recent years and know how important that is. The gut is closely linked to the brain, so negative changes in the gut microbiome can result in symptoms such as brain fog, depression, and anxiety.

In reality, though, you can pick any organ and it most likely connects to the gut. There’s a gut-thyroid axis, gut-liver axis, gut-skin axis, and even the gut-lung axis, among others. Problems with digestion really do cause problems with an individual’s overall health.

Here we’re going to be talking about microbial dysbiosis, which is when we have some divergence in the microbiota from what we currently know as “healthy” (more on that later). It could be when good (commensal) bacteria decrease and opportunistic (pathogenic or bad bacteria) take hold. It could also just be overgrowths of good bacteria as well!

The gut can be thought of as a large ecosystem, which is why gut health can be so complex. You can think of it almost like a rainforest. The rainforest is incredibly diverse. Thousands and thousands of different species, from the smallest insects to the largest animals, live in a rainforest.

The thing with large ecosystems is that they depend on a precise balance. If one particular predator happens to overproduce or even a new predatory species is introduced, you can have trickle-down effects far down the chain.

If one of the predators overconsumes something smaller on the food chain, but that smaller species just happens to be very important for the overall ecology, then we can have the effect of killing off many species.

For example, there’s a little rodent called an agouti in the rainforest whose teeth are one of the only ones strong enough to break open certain seed pods, and therefore the agouti is responsible for replanting trees. If they were to go extinct or become overhunted, then the population of many different trees would decrease. If these trees feed other animals, and those other animals feed other animals, then a lot of disruption occurs within the ecosystem of the rainforest.

The point here is that the gut microbiome is much like this. You want to have just the right amount of diversity within the gut microbiome to maintain optimal health. When certain species of gut bacteria go out of balance, it can have large trickle-down effects with other gut species, and many effects outside of the gut.

What is Dysbiosis?

Simply put, bacterial dysbiosis is some sort of negative alteration of your gut’s microbial balance. This can be a reduction in overall microbial diversity — meaning the number of species of bacteria in the gut significantly decreases.

Dysbiosis can be a loss of beneficial bacterial species as well as a rise in harmful ones. In practice, a dysbiotic microbiome usually has all of these traits: decreases in diversity, fewer beneficial bacteria, and more bad (pathogenic) bacteria.

Sometimes the bacteria aren’t even necessarily pathogenic; sometimes, under normal circumstances, and when they’re in balance, they’re helpful and healthy, but in other circumstances, when the balance is disturbed, they become harmful to an individual’s health.

Think back to the rainforest analogy. A rainforest with only 10–20 species instead of thousands means that keystone species are gone, causing many other species to go extinct. Trees are dying and not being replanted, and you have these 10–20 species romping around a dying area. Not a very healthy rainforest, right?

Since the gut microbiome has been proposed to be a key modulator of human health, many researchers actually consider it to be an ‘essential organ’ of the human body.

Potential Health Effects of Dysbiosis

Now that we’ve established what it is, let’s dive into the potential health consequences of dysbiosis, starting with the local environment: the gut.

Increased Intestinal Permeability or Leaky Gut

If you want a deeper dive into leaky gut, refer to the earlier entries in this gut health blog series. In a nutshell, a leaky gut is when there is increased intestinal permeability, which allows partially digested proteins and portions of bacteria cells into the bloodstream, which can cause systemic inflammation.

A healthy microbiome is very protective of the intestinal lining. For some examples, many types of bacteria create short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from fiber, which basically build up the mucus lining in the gut, protecting the intestinal cells underneath. SCFAs also provide fuel for colonocytes (the epithelial cells that line the colon) and have numerous systemic effects, including beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity and appetite control.

Gut bacteria also create post-biotics (metabolites from processing food) that protect the gut as well. For example, polyphenols, compounds found in fruits and vegetables, get processed by bacteria into many diverse molecules which have been shown to protect against inflammation-induced intestinal permeability (aka leaky gut).

Some species of healthy intestinal bacteria actually upregulate the genetic expression of proteins that are responsible for the tight junctions that hold our intestinal cells together. If those bacteria are not present or there are not enough of that beneficial bacteria, an individual can end up with a leaky gut.

I think you can see what might happen if these gut bacteria are lower or gone — we get increased intestinal permeability and, therefore, systemic inflammation.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

We already halfway answered this with the first point about leaky gut, since increased intestinal permeability is also seen in most, if not all, cases of IBS.

Whenever we assess the microbiome of someone with IBS, we see that it’s heavily altered compared to someone with a healthy gut microbiome, and this could contribute to the associated symptoms of IBS — namely diarrhea or constipation, depression, and brain fog, bloating and gas, and GERD, among others.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO, by definition, is dysbiosis that generally occurs within the first half of the small intestine. The small intestine is normally lower in microbes in general compared to the large intestine, since we have many antimicrobial substances going through the small intestine, such as bile acids.

The small intestine does most of the absorption of nutrients, and the large intestine does most of the fermenting of fibers. However, if harmful bacteria are allowed to take hold and overgrow, then we see a lot of the same symptoms that we do in IBS, including diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and gas.

Autoimmune Disease

This is the point where gut health connects to the rest of the body. An individual with gut health issues, such as gut dysbiosis, can experience inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which is a good segway to autoimmune disease in general since IBD is autoimmune in nature.

IBD is an umbrella term that encompasses two illnesses: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Crohn’s can create lesions and destruction along any point of the digestive tract from the mouth to the colon, whereas ulcerative colitis damages the tissue in the colon.

Autoimmune disease, as the name suggests, is when the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. A healthy microbiome has significant roles in keeping the immune system healthy and self-tolerant, meaning it helps the immune system recognize the body’s own tissues as its own tissues and not a foreign invader.

About 70% of the immune system is located in the gut, and your gut microbes actually have a role in training what type of immune cells will mature, and what kind of cytokines will be released.

Cytokines are signaling molecules that tell your immune system to either create inflammation (pro-inflammatory cytokines) or dissipate inflammation (anti-inflammatory cytokines). A healthy gut microbiome trains immune cells to keep these in a healthy balance.

Dysbiosis has been connected to many autoimmune diseases, from Hashimoto’s to multiple sclerosis to Lupus.

Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Metabolic Disease

People who deal with obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease have a different dysbiotic profile compared to healthy individuals. Chronic hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia have been shown to cause dysbiosis as well as increased intestinal permeability, which can then aggravate any systemic inflammation that’s already occurring and further damage an individual’s gut health.

There is considerable evidence in mice and a decent amount of data in human studies that dysbiosis may cause obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease.

Something we’ve seen in scientific studies is that if you take an obese mouse with insulin resistance and transfer their microbiome to a lean germ-free mouse (this is a completely sterile mouse without a microbiome at all), the previously germ-free mouse will get obese and develop insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes. This has been replicated numerous times over the years.

We have a ton of data about how the gut microbiome can indirectly contribute to insulin resistance. Inflammation in the body causes insulin resistance, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can travel through the portal vein to the liver and contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which induces liver insulin resistance, and there are many more ways the bacteria in the gut can impact an individual’s insulin resistance and overall health.

There are also a few published case reports of this happening in humans in the case of fecal transplants. Fecal transplants are done in Western medicine to combat antibiotic-resistant C. Diff (a germ that causes diarrhea and colitis), which can be exceedingly hard to get rid of. There are a few reports of those who got fecal transplants taking on many characteristics of the fecal donor.

One woman, who was a lean marathon runner before her transplant, gained significant amounts of weight and exhibited insulin resistance after her fecal transplant, and she claimed she did not change her diet or amount of exercise at all. This begs the question if it goes the other way around, and eventually, we might start banking the poop of athletes and healthy individuals for use in trying to improve the health of unhealthy individuals. This certainly isn’t the case yet, so don’t jump the gun and go on a quest for Tom Brady’s poop. More research is definitely needed on this topic.

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease

If dysbiosis increases the risk of or can potentially cause obesity and metabolic disease, then it makes sense that it would also affect cardiovascular disease. Metabolic disease and cardiovascular disease are closely linked. For example, the highly elevated triglycerides, small particle LDL, and inflammation seen in metabolic disease can cause the hardening and thickening of arteries that is caused by plaque buildup.

Studies show an altered microbiome in individuals with cardiovascular disease looks very similar to those individuals who have a metabolic disease. The germ-free animal model has been used here, too; when a rat with hypertension had its gut microbiome transplanted into a germ-free mouse, the previously germ-free mouse then developed hypertension as well. This was an animal study, so, as always, take it with a grain of salt, but given we have some human case reports on metabolic disease, it might be the cause here as well.

Other Effects of Dysbiosis

I won’t go too in-depth here, but just for a complete profile, dysbiotic microbiomes have been viewed in PCOS, cancer, Alzheimer’s, gout, osteoarthritis, liver disease, and others. All of these potential illnesses and diseases are why it’s essential that, as fitness coaches, we look out for our clients and ensure they have a healthy gut.

Potential Causes of Dysbiosis

Many things across your lifespan affect your gut microbiome and can influence dysbiosis, and it starts from the moment you’re born.

This section will cover several possible causes of dysbiosis and the negative impacts it can have on an individual’s gut microbiome.

Birth and Breastfeeding

Whether you came into this world through vaginal birth or C-section, birth influences how your microbiome develops and the core of what it will be in adulthood.

Exposure to the microbiome of the vaginal canal contributes to cementing the microbiome of the baby. Additionally, whether you were breastfed or formula-fed also matters. There are tons of prebiotics and microbes found in breast milk that further establish and cement an infant’s microbiome.

Hygiene Hypothesis

Growing up, the environment a child is exposed to matters.

Did they play outside a lot, getting exposed to dirt, trees, etc.? Were they around a lot of animals, such as pets, when they were younger? These types of activities can influence the microbiome in a positive manner as well.

In fact, the observations that children who grew up on farms had significantly lower rates of allergies and autoimmune disease spurred what’s known as the “hygiene hypothesis,” which basically states that the level of sterility we live with today with less exposure to the elements and microbes creates a less diverse and healthy microbiome and immune system.

Drugs and Dysbiosis

Many drugs influence the microbiome, and the number one culprit here is obviously antibiotics. Significant antibiotic use will 100% induce dysbiosis transiently in all cases. For some, the microbiome recovers rather quickly, but for many, these are lasting changes that can, unfortunately, take a long time and a lot of work to improve.

Other drugs that may contribute to dysbiosis include proton pump inhibitors, corticosteroids, NSAIDs (e.g., aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen), opioids, statins, and antipsychotics.

It would be wise to discuss a client’s medication history when helping them improve gut health because their risk factor will be higher than that of an individual who does not have a history of taking medications.

Lifestyle May Cause Dysbiosis

Honestly, in nearly all cases of activities we know are bad for overall health, we see negative microbiome changes as well.

This includes sleep deprivation, chronic stress, and a standard American diet — you know, a diet high in ultra-processed foods and a diet consisting of high sodium, fat, and sugar.

Diet is obviously going to be a large one, but maybe not in the most direct way you might think. Yes, a fiber-poor diet can starve certain microbes and allow others to take hold. Yes, processed foods can contribute to the overgrowth of bad bacteria. These would be direct modulations.

But data from scientific research suggests that if you change the health of the individual, the microbiota changes, and vice versa; even cigarette smoking has been shown to bring about a dysbiotic microbiome.

How to Treat Dysbiosis

While I cannot offer you any guarantees, because every individual and their circumstances are unique, I can offer you potential solutions that have made significant differences in the gut microbiome of individuals I and my fellow coaches have worked with in the past.

Going way in-depth on gut health protocols is beyond the scope of this blog post, but if you look at the causes, you can most likely reverse-engineer a solution to help your client improve their gut microbiome and their dysbiosis.

While you can’t exactly go back in time and change how you or your client were born or if you were breastfed, nor if you took doxycycline (antibiotic) for acne for years, like a lot of people did, there are certain things that you can do.

The first step is the mastery of the basics. This would be keeping processed food intake minimal, ditching the high sugar diet, making the majority of what you eat come from whole, nutrient-dense foods, eating a diverse array of fiber-rich vegetables, getting adequate hydration and adequate exercise, getting a solid 8 hours of sleep per night, managing your stress, and taking walks after meals.

Now, this is a bit different if gut disease, multiple gut issues, and dysbiosis are already present. For example, you may actually have to avoid certain fibers, such as FODMAPS, in order to starve off some harmful bacteria.

Going in-depth on how to resolve even the toughest of gut issues is exactly what we do inside of the Functional Nutrition and Metabolism Specialization, so please check that out if you’d like to learn more. Click here for more information about what we offer and how you can use this information to help your clients improve gut health issues such as dysbiosis, leaky gut, and more.

Summary of Dysbiosis:

- The microbes in your gut affect its health, and the health of your gut affects most other organs – the brain, the heart, the thyroid, the liver, and others.

- Dysbiosis is simply a deviation from what we understand as a healthy microbiome — either significantly decreased diversity, overgrowth of bad bacteria and loss of good ones, or all of the above.

- Dysbiosis has been observed in all gut conditions, obesity, autoimmune disease, depression and anxiety, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and metabolic disease, and other diseases, and may actually be the cause of some of these.

- A healthy microbiome starts when you’re born. It’s influenced by vaginal vs. C-section birth, whether you were breastfed or formula fed, and whether you were exposed to dirt, animals, etc, when you were younger. Then all things that affect the health of an individual potentially affect the microbiome, including poor sleep, high stress, poor diet, sedentariness, and others.

- To keep your microbiome healthy, do the opposite of what I just said in point 4. Moderate stress, get good sleep, minimize processed foods, include a very wide variety of fibrous vegetables – the more variety the better, and just generally eat mostly whole foods.

Check out my other gut health posts to dive deeper into this topic and learn how to improve overall health by addressing your gut:

References

Rui-Xue Ding et al. Revisit gut microbiota and its impact on human health and disease. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. Volume 27, Issue 3, July 2019, Pages 623-631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2018.12.012

Katherine R. Amato, Marie-Claire Arrieta, Meghan B. Azad, Michael T. Bailey, Josiane L. Broussard, Carlijn E. Bruggeling, Erika C. Claud, Elizabeth K. Costello, Emily R. Davenport, Bas E. Dutilh, Holly A. Swain Ewald, Paul Ewald, Erin C. Hanlon, Wrenetha Julion, Ali Keshavarzian, Corinne F. Maurice, Gregory E. Miller, Geoffrey A. Preidis, Laure Segurel, Burton Singer, Sathish Subramanian, Liping Zhao, Christopher W. Kuzawa. The human gut microbiome and health inequities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Jun 2021, 118 (25) e2017947118; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2017947118

Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015 Feb 2;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191. PMID: 25651997; PMCID: PMC4315779.

Wilkins, L.J., Monga, M. & Miller, A.W. Defining Dysbiosis for a Cluster of Chronic Diseases. Sci Rep 9, 12918 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49452-y

Vijay, A., Valdes, A.M. Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Nutr (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00991-6

Jason Martinez et al. Unhealthy Lifestyle and Gut Dysbiosis: A Better Understanding of the Effects of Poor Diet and Nicotine on the Intestinal Microbiome. Front. Endocrinol., 08 June 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.667066

Elena Scotti et al. Exploring the microbiome in health and disease: Implications for toxicology. Toxicology Research and Application. First Published December 10, 2017 Review Article. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397847317741884

Grace A. Ogunrinola, John O. Oyewale, Oyewumi O. Oshamika, Grace I. Olasehinde, “The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health”, International Journal of Microbiology, vol. 2020, Article ID 8045646, 7 pages, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8045646

Chakaroun RM, Massier L, Kovacs P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients. 2020 Apr 14;12(4):1082. doi: 10.3390/nu12041082. PMID: 32295104; PMCID: PMC7230435.