At this point, most people working in the health and fitness industry know not to dismiss the importance of high-quality sleep.

The importance of sleep has become widespread in the health and fitness industry and even in the mainstream conversation of those not in health and fitness. Information about sleep quality and quantity is showing up on more and more client intake forms and check-in sheets, and for good reason. Sleep impacts health in more ways than you might realize!

For those not familiar, sleep deprivation can lead to a host of short- and long-term consequences, including irregularities in thyroid function, adrenal health, gut health, and a client’s overall ability to improve their physique and overall health.

Sleep loss lowers satiety hormones, raises hunger hormones, tanks testosterone in men, and much more.

Table of Contents

Sleep Hygiene Basics

If only it was as easy as telling your clients to get 8 hours of quality sleep. Many people have a hard time falling asleep, struggle with insomnia, and much more. This largely has to do with the high-stress environment of the modern world.

There are certain baseline sleep and circadian hygiene practices that help with improving sleep. The basics of good sleep hygiene include:

- Getting as much morning sunlight exposure to the eyes as possible within 30–60 minutes of waking (get at least 10 minutes).

- Use blue light-blocking glasses after the sun goes down (just walking around your house, this isn’t only relegated to electronics use).

- Cut off electronics 1–2 hours before bed.

- Keep your bed and bedroom only for sleep and sex (no working there).

- Keep your sleeping environment as dark and cool as possible (the optimal temperature for sleep quality in studies is 67° F – it should feel chilly if you’re not under the covers).

- Stop eating 2–3 hours before bed.

- No high intensity workouts within 2-3 hours of going to bed.

What happens, though, when you or your client is doing all of the above perfectly and is still struggling to either fall asleep, getting night wakeups, or still feeling unrested upon waking?

Overlooked Reasons for Insomnia and Poor Sleep

1. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

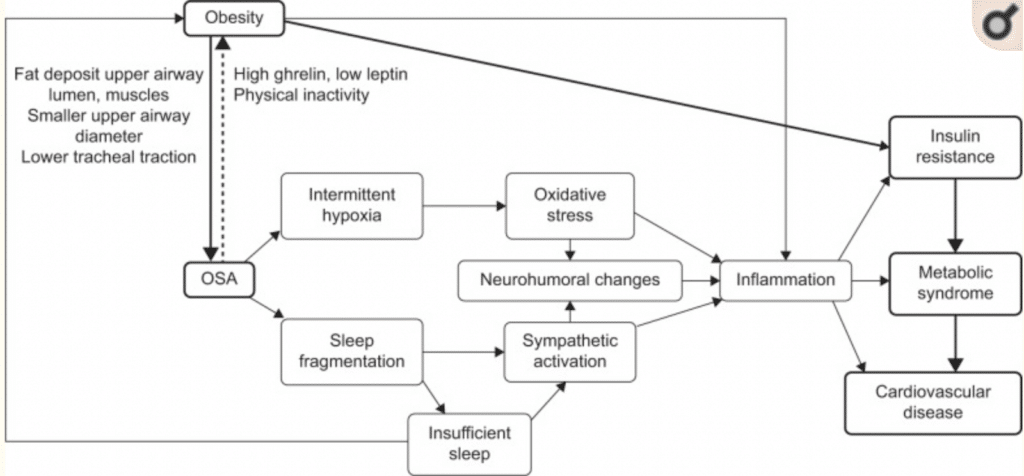

OSA is caused by upper airway obstruction during sleep, and it’s more common and more problematic than you might think. During these episodes, our blood oxygen saturation falls, which can lead to autonomic dysregulation (explained below).

Regulation of the autonomic nervous system is vital for health; this means being in a fight-or-flight state at the appropriate time (working out, when facing a threat, etc.) and being in a rest-and-digest state at the appropriate time (the other 20+ hours of the day).

The autonomic dysfunction that can occur during OSA basically puts people in a stressed state 24/7, making it nearly impossible to manage stress correctly from a physiological point of view.

Over time, these acute changes lead to increased risk of many chronic conditions, like insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and neurocognitive disease. According to a review by Benjafield et al. that looked at OSA in over 16 countries, approximately 1 billion people aged 30–65 are affected by it, and 425 million of those are deemed to have moderate to severe OSA.

This is a seriously overlooked factor that may be keeping overweight or obese individuals from getting the physique and health results they want. If you have an obese or high lean mass/large-necked client (such as a bodybuilder), it should be a priority question to ask them if they’ve ever done a sleep study and, if not, ask if they snore and/or if their partner or spouse has noticed they stop breathing at night. These are tell-tale signs.

OSA produces a chronic inflammatory state, which leads to increased thickening of the arteries. Similar to obesity, which is also considered a low-grade inflammatory state, OSA has been shown to stimulate fat tissue to produce inflammatory cytokines, causing inflammation.

OSA leads to sleep fragmentation, low oxygen, and increased carbon dioxide in the blood, which stimulates increased sympathetic activity and increased RAAS signaling, both of which will result in high blood pressure, increased systemic inflammation, and increased oxidative stress. The end result of these changes is endothelial dysfunction (a type of coronary artery disease) and metabolic dysfunction, which accounts for the increase in cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Risk factors for OSA:

- Obesity and high BMI are the biggest independent risk factors

- Neck circumference greater than 17 inches (43cm) in men and 15 inches (38cm) in women, irrespective of BMI

- Being male or a postmenopausal woman (estrogen/progesterone have roles in maintaining good upper airway tone, and progesterone opens airways)

- Being over 50 years old

- Being on testosterone replacement therapy

- One study tracked men as they began TRT, doing a sleep study before and a sleep study after. Prior to TRT, none of the men had sleep apnea. After beginning TRT, 52% of the men developed sleep apnea.

- Drinking alcohol can worsen OSA in those who already have it by causing increased relaxation of the upper airway, contributing to upper airway collapse.

- Eating large meals closer to bedtime also causes increased relaxation of the upper airway.

Treatment Options

The biggest effect will be reducing body fat levels to a healthy range. For many people, this will get rid of their apnea, however, folks with apnea may need treatment to help reach their weight loss goals, given that OSA will reduce overall daytime energy levels and produce an inflammatory state.

For that, the gold standard is a CPAP machine; CPAP stands for continuous positive airway pressure. The machine delivers a stream of oxygenated air into the lungs during sleep. Treatment with a CPAP has been shown to alleviate many negative side effects associated with sleep apnea.

Mandibular advancement devices (MADS) are another option. These are little devices you place in your mouth that work by forcing the jaw and tongue forward during sleep.

In studies, it doesn’t show as much effectiveness as a CPAP in reducing high blood pressure and other risk factors associated with sleep apnea, but it does improve them over no treatment.

2. Dietary Sensitivities and Gut Dysbiosis

The gut influences most of our physiology, and in this case, it influences sleep as well through the gut-brain axis. Symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea can interrupt sleep from physical discomfort, but even if gut-related symptoms aren’t present, dysbiosis can still potentially lead to issues with insomnia.

Dietary intolerances can also elevate histamine, which is a wake-promoting chemical, amongst other things.

So does sleep deprivation alter the microbiome, or does the dysbiosis of the microbiome alter sleep? It might be both. Surprisingly, not many studies have been done looking at the effects of sleep restriction on the microbiome, but the ones that have been done have conflicting results.

In two studies looking at sleep deprivation’s effects on the microbiome, one study looked at 9 healthy men and sleep-restricted them over the course of two nights and looked at fecal microbiome samples before and after. The men had a slightly higher Fermiculites to Bacteroidetes ratio after sleep restriction, which is considered to be more towards an “obesogenic” microbiome profile.

However, another study of 11 men who were restricted to 4 hours of sleep for 20 days showed no significant changes in microbiome status as measured by fecal microbiome samples before and after sleep restriction, so we have some conflicting data.

Both of the studies used the same testing methods as well.

We do, however, have a solid piece of literature looking at the converse of how dysbiosis affects quality sleep and sleep architecture. This particular human randomized controlled trial used actigraphy (basically, a Fitbit or Apple watch) to quantify sleep measures coupled with gut microbiome sampling to determine how the gut microbiome correlates with various measures of sleep physiology.

The study discovered a link between the variety of bacteria in the gut and improved sleep quality, including fewer instances of waking up during the night and faster sleep onset. When analyzing the types of bacteria present, they found that higher diversity of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes was associated with better sleep efficiency, as well as improved lateral thinking and abstract thinking abilities. On the other hand, specific bacteria taxa like Lachnospiraceae, Corynebacterium, and Blautia were negatively associated with all sleep measures.

Dysbiosis can induce insomnia and lower-quality sleep. This is further cemented by looking at studies that tested the effects of probiotics on insomnia.

If someone has bad dysbiosis, then a whole gut protocol may be needed, but an easy way to look at changes in the microbiome and its effects on sleep in studies would just be probiotic supplementation since we know that it’s going to alter microbial composition of the gut.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 38 healthy volunteers assigned to an experimental or control group assumed a daily dose of a probiotic mixture or a placebo, respectively, for 6 weeks. Mood, personality dimensions, and sleep quality were assessed four times (before the beginning of the study, at 3 and 6 weeks, and at 3 weeks after completion).

A significant improvement in mood was observed in the experimental group, with a reduction in depressive mood state, anger, and fatigue, and an improvement in sleep quality only after 6 weeks. Meaning they didn’t see the benefit in sleep until they’d been supplementing for 6 weeks.

Histamine issues can also result in insomnia. If you’re histamine intolerant, this would be a big contributor. But in general, dietary sensitivities have the ability to increase histamine secretion in the body, which promotes wakefulness.

If someone has bad gut issues, you probably don’t just want to throw probiotics at it and call it a day; it’ll probably take more than that. The study above was just to illustrate that changing the composition of the gut microbiome can improve sleep.

A better approach would be cleaning up someone’s diet to eating mostly whole, micronutrient- and fiber-dense foods. If that doesn’t fix the issue, then you’ll be looking at a 4R/5R elimination diet protocol with the use of probiotics, enzymes, and antimicrobials if needed. Also, be on the lookout for histamine intolerance: reactions to leftover foods, fermented foods, cured meats, etc.

3. Micronutrient Deficiencies or Excesses

A large 2017 review study looked at micronutrient deficiencies associated with poor sleep patterns and insomnia. In the articles reviewed, researchers generally supported that deficiencies or suboptimal levels of iron, magnesium, and vitamin A may disrupt sleep, and repletion of these may improve sleep quality.

Micronutrient status has also been linked to sleep duration, with a longer sleep duration linked with adequate iron, zinc, and magnesium levels and shorter sleep duration was associated with elevated copper.

On the other hand, potassium and vitamin B12 supplements before bed increased the time to fall asleep and increased night wakeups. The mechanisms underlying these relationships include the impact of micronutrients on excitatory/inhibitory neurotransmitters and the expression of circadian genes.

For example, retinoic acid, a metabolite of vitamin A, regulates the expression of two core circadian genes, CLOCK and BMAL1. Magnesium, iron, and zinc play roles in suppressing excitatory neurotransmission. Ensuring appropriate levels of micronutrients is important here, and you may want to avoid taking any large supplemental doses of B12 or potassium before bed.

Foods containing them are fine, this is more for large supplemental doses.

4. Blood Sugar Instability Throughout the Night

Blood sugar instability throughout the night and even a drop back to baseline from a blood sugar high can cause increased night wakeups and decreased sleep quality. When blood sugar drops, this causes a release of glucagon and catecholamines to increase blood sugar. All of these hormones may cause sleep disturbances.

The obvious individuals who might suffer from these things are individuals with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, or type 2 diabetes. The response of glucose and insulin to a meal in an individual with metabolic syndrome may result in reactive hypoglycemia (low blood sugar episodes) regardless of the time of day.

The loss or dampening of first-phase insulin response in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes results in an exaggerated second-phase insulin response which can drop blood sugar below baseline.

If this particular client has any sized meal with carbohydrates before bed, they may suffer from low blood sugar, causing the above hormones to suddenly elevate. This may be one reason that time-restricted feeding with an earlier eating window (stopping eating at 6 p.m.) instead of a later eating window (2 p.m.–10 p.m., for example) may be more beneficial from a health standpoint for those with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes as opposed to the average healthy individual.

Since the last meal is many hours before bed, this gives the chance for blood sugar to drop and stabilize before going to bed.

Your body notices relative changes rather than absolute levels. Even if your blood sugar doesn’t drop below baseline, a decrease from a high level can still cause sleep disturbances due to increased glucagon and catecholamines. For a person without insulin resistance, this would likely require eating a larger meal before bedtime, which can disrupt sleep quality regardless of its impact on blood sugar.

For the individual with advanced insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes, it would be best to either stop eating 3–4 hours before bed or, if they’re very hungry, having a high protein, low-moderate carb with low GI snack before bed would be okay.

5. Imbalanced Estradiol and Progesterone

Estradiol and progesterone play important roles in the regulation of sleep.

Animal studies have verified that progesterone can alter the sleep pattern as an agonist of the GABA-A receptors. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that’s associated with relaxation, and if we agonize the GABA receptor, we’re activating it, which is a good thing in this context.

In any case, it is very likely that progesterone does not act directly on GABA-A receptors, but rather involves the activity of a progesterone metabolite named allopregnanolone.

Evidence coming from estrogen replacement therapy suggests a hypnotic effect since it relieves most of the sleep-related complaints of perimenopausal women. Additionally, data on rodents suggest that estrogen seems to have an important effect on the consolidation of the sleep-wake cycle, as ovariectomized female rats treated with estrogen display a better balance of sleep when compared with the controls.

In this case, estrogen promoted both REM and non-REM sleep during their natural sleep cycle and reduced it during the time they were awake.

It has also been suggested that estrogen may exert its effects through progesterone, as adequate/increased estradiol levels have been shown to increase levels of progesterone receptors.

However, excess estrogen, or when estrogen is out of balance with progesterone, has also been shown to increase glutamate neurotransmitter signaling. Glutamate is one of the brain’s principal excitatory neurotransmitters, so this can also result in anxiety, irritability, and insomnia.

We can see this across the normal menstrual cycle, as well. Evidence suggests that sleep is mostly disturbed during the mid-late luteal phase when steroidal hormone levels start to decline. During this phase, women tend to experience an increased number of sleep disturbances compared with the follicular phase.

Taken together, these findings connect the impact of hormonal fluctuations with the onset of sleep complaints. The same impact might be seen across the lifespan, as shifts in hormonal patterns observed during puberty, pregnancy, and the menopausal transition are associated with increased insomnia.

All that being said, if a woman has low progesterone and high estradiol, or if both sex hormones are quite low, this will affect sleep. Figuring out the cause could be a greater challenge, but I would gauge an individual’s whole body stress load in terms of overtraining, undereating, gut dysbiosis, obesity and/or insulin resistance, PCOS, systemic inflammation from another source, etc.

Postmenopausal women can consider hormone replacement therapy here as there are numerous studies showing increased sleep quality and quantity from it. When done correctly, there is little risk to estradiol and progesterone replacement post-menopause,

6. Past Trauma

PTSD and past trauma can result in alterations of neurobiology and neuroendocrinology that affects sleep. In fact, long-lasting insomnia is a core factor of PTSD that’s well-known amongst the medical community and in scientific literature.

Lesser traumas that don’t necessarily result in a PTSD diagnosis may also have the same effect. Brain changes in those with trauma include volumetric reductions in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex, as well as functional dysregulation in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex.

When the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex are not functioning properly and the hippocampus is smaller, it leads to increased excitability and a lower threshold for excitation. This makes it much more challenging to relax and calm down.

When the amygdala, a part of the brain involved in processing emotions, remains highly active for an extended period (as seen in post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD), it can contribute to the occurrence of nightmares and impact the neural activity in the sleep-regulating centers of the brainstem and forebrain. The amygdala, along with the hippocampus and ACC (anterior cingulate cortex), plays a crucial role in fear consolidation, fear extinction, and emotional distress. These processes are involved in the generation of nightmares and can influence the functioning of the brainstem and hypothalamic autonomic centers.

Studies show these structural amygdalar alterations are associated with sleep disturbances not only in PTSD patients but also in traumatized controls who do not develop the other criteria for PTSD.

The solution is to deal with the trauma. Easier said than done, I know. Various forms of therapy, from CBT to others, can assist in non-PTSD trauma and also aid in trauma-induced PTSD, although the latter can be tough to treat.

More promising treatments are on the horizon, however, namely MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, which is showing serious promise in phase III clinical trials right now with efficacy miles above any other drug or therapy currently available.

References

Abbasi A, Gupta SS, Sabharwal N, Meghrajani V, Sharma S, Kamholz S, Kupfer Y. A comprehensive review of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Sci. 2021 Apr-Jun;14(2):142-154. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20200056. PMID: 34381578; PMCID: PMC8340897.

Smith RP, Easson C, Lyle SM, Kapoor R, Donnelly CP, Davidson EJ, Parikh E, Lopez JV, Tartar JL. Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS One. 2019 Oct 7;14(10):e0222394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222394. PMID: 31589627; PMCID: PMC6779243.

Benedict C, Vogel H, Jonas W, Woting A, Blaut M, Schürmann A, Cedernaes J. Gut microbiota and glucometabolic alterations in response to recurrent partial sleep deprivation in normal-weight young individuals. Mol Metab. 2016 Oct 24;5(12):1175-1186. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.003. PMID: 27900260; PMCID: PMC5123208.

Zhang SL, Bai L, Goel N, Bailey A, Jang CJ, Bushman FD, Meerlo P, Dinges DF, Sehgal A. Human and rat gut microbiome composition is maintained following sleep restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Feb 21;114(8):E1564-E1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620673114. Epub 2017 Feb 8. PMID: 28179566; PMCID: PMC5338418.

Marotta A, Sarno E, Del Casale A, Pane M, Mogna L, Amoruso A, Felis GE, Fiorio M. Effects of Probiotics on Cognitive Reactivity, Mood, and Sleep Quality. Front Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 27;10:164. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00164. PMID: 30971965; PMCID: PMC6445894.

Atrooz F, Salim S. Sleep deprivation, oxidative stress and inflammation. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2020;119:309-336. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.03.001. Epub 2019 Apr 24. PMID: 31997771.

Kline CE, Hall MH, Buysse DJ, Earnest CP, Church TS. Poor Sleep Quality is Associated with Insulin Resistance in Postmenopausal Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2018 May;16(4):183-189. doi: 10.1089/met.2018.0013. Epub 2018 Mar 20. PMID: 29649378; PMCID: PMC5931175.

Ji X, Grandner MA, Liu J. The relationship between micronutrient status and sleep patterns: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017 Mar;20(4):687-701. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016002603. Epub 2016 Oct 5. PMID: 27702409; PMCID: PMC5675071.

Ikonte CJ, Mun JG, Reider CA, Grant RW, Mitmesser SH. Micronutrient Inadequacy in Short Sleep: Analysis of the NHANES 2005-2016. Nutrients. 2019 Oct 1;11(10):2335. doi: 10.3390/nu11102335. PMID: 31581561; PMCID: PMC6835726.

Bollu PC, Kaur H. Sleep Medicine: Insomnia and Sleep. Mo Med. 2019 Jan-Feb;116(1):68-75. PMID: 30862990; PMCID: PMC6390785.

Bezerra AG, Andersen ML, Pires GN, Tufik S, Hachul H. Effects of hormonal contraceptives on sleep – A possible treatment for insomnia in premenopausal women. Sleep Sci. 2018 May-Jun;11(3):129-136. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20180025. PMID: 30455843; PMCID: PMC6201525.

Nolan BJ, Liang B, Cheung AS. Efficacy of Micronized Progesterone for Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial Data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Mar 25;106(4):942-951. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa873. PMID: 33245776.

Nowakowski S, Meers J, Heimbach E. Sleep and Women’s Health. Sleep Med Res. 2013;4(1):1-22. doi: 10.17241/smr.2013.4.1.1. PMID: 25688329; PMCID: PMC4327930.

Nardo Davide, Högberg Göran, Jonsson Cathrine, Jacobsson Hans, Hällström Tore, Pagani Marco. Neurobiology of Sleep Disturbances in PTSD Patients and Traumatized Controls: MRI and SPECT Findings. Frontiers in Psychiatry, VOLUME 6, 2015, PAGE 134. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00134. ISSN: 1664-0640

Alana M C Brown, Nicole J Gervais, Role of Ovarian Hormones in the Modulation of Sleep in Females Across the Adult Lifespan, Endocrinology, Volume 161, Issue 9, September 2020, bqaa128, https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqaa128

M.W.L. Morssinkhof, D.W. van Wylick, S. Priester-Vink, Y.D. van der Werf, M. den Heijer, O.A. van den Heuvel, B.F.P. Broekman. Associations between sex hormones, sleep problems and depression: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Volume 118, 2020, Pages 669-680, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.08.006.

Hong S, Mills PJ, Loredo JS, Adler KA, Dimsdale JE. The association between interleukin-6, sleep, and demographic characteristics. Brain Behav Immun. 2005 Mar;19(2):165-72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.07.008. PMID: 15664789.