You’ve probably had clients come up to you and ask, “Can stress make you fat?” The answer is a resounding “yes”, but it might not be exactly in the ways that you think.

Chronic stress is exceptionally common these days and it is a vicious cycle, especially for weight gain and mental health. The list of reasons for why someone experiences stress is endless.

Chronic stress could be caused by deadlines at work or just the fact that you really don’t enjoy your job. It could be that you have a new child, or maybe you’re going through some issues with your interpersonal relationships. Unavoidable stressful situations such as your traffic-filled commute in the morning aren’t helping, either.

People can create their own stress as well; ruminating on the same or similar negative thoughts that they can’t seem to let go of.

Regardless, we’re all under stress, and some people experience much more stress than others.

What most people don’t realize is that stress has much farther-reaching consequences than just making you feel overwhelmed or anxious. Everything from cognitive to cardiovascular and physical health are negatively affected by chronic stress.

Chronic stress can lead to weight gain, high blood pressure, and heart disease, which is why it’s essential to find stress management techniques that work for you. Chronic stress can even impact your mental energy!

Table of Contents

How Chronic Stress Affects the HPA Axis

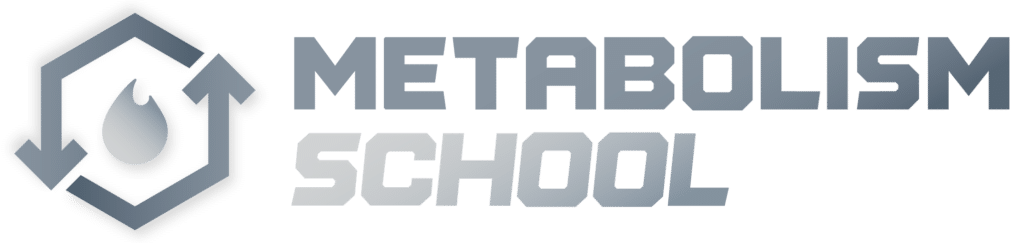

Before we dive into how stress can make you gain weight, let’s zoom out and start with a bit of general education on stress hormones and the HPA axis. The HPA axis is one of the primary hormonal axes that regulate our stress response. This stress hormone is called cortisol. There are others, such as the catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), but we’ll focus on cortisol levels and the HPA axis first.

Whenever we’re under stress, the body is essentially in fight or flight mode, so the hypothalamus releases a compound called CRH that gets sent to another area of the brain — the pituitary gland. This gland sends out a hormone called ACTH, which then communicates to our adrenals to make the stress hormone cortisol. Next, cortisol gets released and has its effects on the body.

Acute increases in cortisol levels are not always a bad thing. It wakes us up in the morning, gives us energy during exercise, and is anti-inflammatory. However, when cortisol levels are chronically high, as in chronic stress, we see an entire slew of negative effects happening all across the body, including weight gain, sleep deprivation, emotional eating, and a negative mood.

Going through chronically elevated cortisol’s effects on the entire body would be a several-day masterclass, so in this post, we’re going to focus on all things metabolic health, meaning insulin sensitivity and nutrient partitioning, which ultimately translates to how stress can make it harder to maintain a healthy weight or build lean muscle mass.

While we won’t touch on how stress causes high blood pressure or heart disease in this particular blog post, we’re going to take it organ by organ, showing the effects of chronic stress on the brain, fat tissue, muscle mass, and the liver.

Chronic Stress and Your Metabolic Health

Most of us face one or more stressors every day. Psychological stress can impact brain, liver, and muscle health and lead to weight gain in chronically stressed individuals.

How Stress Levels Affect The Brain

The brain is the ultimate command control center. Although we have hunger hormones and satiety hormones that result in being hungry or feeling full, all of these act through changing the activation of certain sets of neurons in the brain.

The main set of neurons in the brain that stimulates hunger is called Agrp/NPY neurons. Ghrelin, our primary hunger hormone, acts on these to make us hungry.

However, cortisol also increases the activation of NPY neurons, which then drives appetite and cravings as well as decreases daily energy expenditure, meaning it can make you stress eat. This activation of NPY neurons by cortisol also stimulates the pancreas to release more insulin, which, over time, can negatively affect our insulin sensitivity and lead to weight gain.

The first effect of chronic stress in the brain as far as metabolic health goes is that it’s going to screw up your hunger and satiety signals, resulting in cravings and making it harder to stick to your diet and eating more calories than you intend, which can be especially challenging if you’re working on a weight loss goal.

The stress hormone cortisol can decrease your appetite for healthy foods and stimulate your appetite for ultra-processed, hyper-palatable foods, which often ends up playing out in our clients as little food consumption during the day and going off the rails with food and snacks at night.

This can result in overeating, weight gain, and the accumulation of visceral fat, which is associated with an increased risk of metabolic disorders.

High Cortisol Levels Increase Fat Tissue (Adipose)

When most people think about fat tissue, they think of the type of fat that most people want to lose; the fat that’s right underneath our skin that hides all of our muscle definition and curves.

Another type of fat that’s significantly worse for our health is visceral fat (some refer to this as toxic fat); this is fat that’s stored around the organs. Visceral belly fat is particularly heinous; the fat that we store around the organs in our abdominal cavity. Chronic stress, and therefore chronically high cortisol, pushes fat storage to visceral fat.

Have you ever seen someone who doesn’t exactly look overweight but has a gut? Maybe their gut is also particularly hard to the touch, like a bowling ball. This is a great example of how stress and weight gain are interconnected. That person probably has a good amount of visceral fat being stored in their abdominal cavity. Alcoholics frequently have this look.

Visceral fat continuously spits out fatty acids into the bloodstream and also straight to the liver through the portal vein. If the amount of fatty acids being spat out overwhelms the speed at which other tissues are taking it up and burning it, then we get significantly more insulin resistance which can lead to gaining unwanted pounds.

Fat can also potentially build up in the liver, resulting in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and also hampers the liver’s insulin sensitivity. This increase in fat and triglycerides can also induce muscular insulin resistance as well.

Elevated Cortisol Levels Affect Muscles

Our muscle tissue is basically our sink for glucose; up to 70% of our glucose disposal from the bloodstream is due to our muscles. However, chronic stress directly decreases glucose uptake into the muscle, leading to higher blood sugar.

Since the glucose isn’t getting taken up by the muscle, it has to go somewhere. This decrease in glucose uptake leads glucose back to the liver to be turned into fatty acids. The liver attempts to package these into triglycerides and spits them out into circulation and the increase in systemic triglycerides can also cause lipid buildup in muscle, causing further insulin resistance.

Not only that, but cortisol highly increases muscle protein breakdown. Whenever we’re trying to build muscle, we always have to consider the balance of muscle protein breakdown vs. muscle protein synthesis, and chronic stress is going to lead to more breaking down of muscle.

Meaning elevated cortisol levels can hinder the body’s ability to repair muscle tissue after physical activity, which can result in slower muscle recovery, prolonged muscle soreness, and increased risk of muscle strains or injuries.

Stress Impairs Liver Health

The liver is an extremely important organ that performs hundreds of functions for our body. If you’ve been keeping track so far, there are many aspects of chronic stress that can cause fat buildup in the liver.

We have fatty acids coming from visceral fat tissue, but then also fatty acids being created from glucose within the liver. This doesn’t even take into account the fatty acids we’re eating, which could further exacerbate things.

This will not only destroy liver insulin sensitivity but hamper many of its other functions as well, causing significant oxidative stress and inflammation.

Chronic stress and elevated cortisol also drive gluconeogenesis, or the creation of glucose. In normal physiology, when we’re not stressed, gluconeogenesis is generally occurring after we haven’t eaten for a while, which helps keep our blood sugar at good levels.

However, even if we’ve just eaten a meal with glucose if our cortisol is very high and we’re quite stressed, we could be creating glucose inappropriately, adding to the glucose load from our meal. Now imagine how eating habits impact this. Someone who gives into their sugar cravings on a regular basis will experience stress related weight gain as their glucose load increases even further.

Stress-Related Weight Gain

Let’s piece this all together, starting with visceral fat. Chronic stress is going to cause more visceral fat storage, which is continually spitting fatty acids into the bloodstream and to the liver.

The muscle tissue is trying to take up these excess fatty acids and triglycerides, but since it can’t burn them as fast as its taking them up, this causes muscular insulin resistance. The products of muscle protein breakdown fueled by cortisol travel back to the liver to create glucose.

Since all the stress made us insulin resistant, the glucose that’s being created in the liver and also coming in from our meals isn’t being taken up as readily by our muscles, so it goes back to the liver to be turned into fat to be stored.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver is mainly driven by the balance of “fat in” versus “fat out” or the fat coming into the liver vs. the fat being exported, and, in this situation, we have a lot of sources that elevate the “fat in” portion. Fat is coming from visceral fat, from our meals, from the creation of fat from glucose, and potentially from our fat tissue under the skin, depending on how insulin resistant we are.

All the while, the brain is causing us to be hungrier and crave more comfort food, in addition to increasing insulin secretion by the pancreas.

Even if you are able to maintain a caloric deficit while highly stressed, your muscle recovery will be significantly reduced because of the increased muscle protein breakdown, and you’ll be in a body that really wants to hang onto its fat stores and use its muscle breakdown for energy while in a deficit.

On top of that, many chronically stressed people suffer from insomnia and have poor sleep quality, so if we put that in the mix too, we have all sorts of hormonal issues that can occur that worsen all of this to make us gain weight.

Lower Stress and Improve Your Health

Feeling stressed is an inevitable part of daily life, but we can manage stress through many techniques. Some common stress reduction techniques that you or your clients may find helpful include meditation, deep breathing, art, music, walks in nature, exercising regularly and just scheduling fun things you enjoy, all of which will also help with your overall mental health.

And, of course, avoiding stressful events wherever possible (for example, if you know that going to an event you aren’t even looking forward to will lead to an argument with someone there, you might as well find something else to do that night).

The best way to avoid stress and weight gain related to too much stress is parasympathetic activation and getting your head out of rumination mode (worrying about the future, past, or even immediate situations) and into the moment of exactly what you’re doing.

While sometimes you can’t help but reach for comfort food when you’re feeling stressed, trying to go for relatively healthier comfort foods rather than high calorie foods, such as air popped popcorn, or practicing mindful eating will help with food intake and weight gain reduction.

I have a podcast all about stress management techniques, so please check that out for further information.

References

Geer et al. Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced Insulin Resistance. Journal of endocrinology and metabolism. REVIEW ARTICLE| VOLUME 43, ISSUE 1, P75-102, MARCH 01, 2014. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.10.005