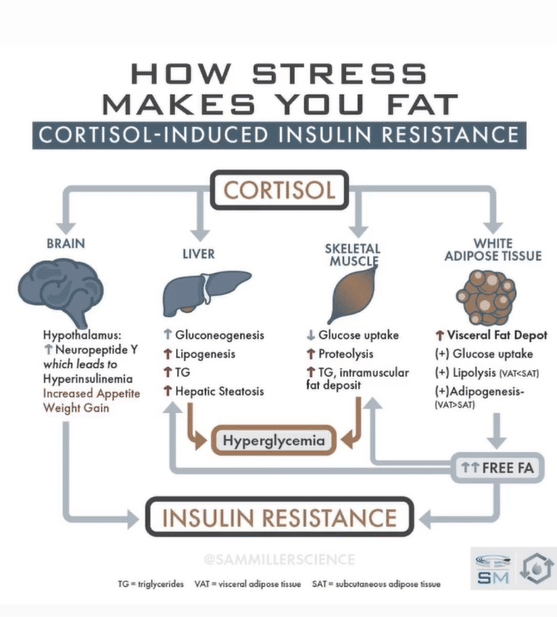

As a fitness coach, you know how important it is to manage stress in client transformation. Stress manifests from many different sources, from physical to emotional, and not only is stress management essential for your client’s overall physique and body composition goals, but it’s also incredibly important for overall health.

Today, we’re going to look at how stress affects appetite. I see this coming up a lot within the fitness industry in conversations related to nutritional planning and conversations around dietary decision-making, and there’s some conflicting information out there.

Table of Contents

What Stress Can Do to Your Appetite

I’m sure you’ve gone through a stressful period in your life; maybe you had a deadline coming up at work that necessitates 60–80 hour work weeks, which puts tension on your relationship. Maybe this is you right now.

Think back to how your appetite was affected during that period. Maybe stress caused you to overeat or crave certain hyper-palatable foods, or, on the other side of the spectrum, it’s possible you lost your appetite and were maybe even undereating relative to your nutrition goals.

In this article, we’ll be talking about appetite changes and other effects you or your clients might experience.

Overeating and Undereating Due to Stress

Think about how your appetite has been affected in the past.

There’s a good chance you experienced under-eating followed by over-eating, which is what most people experience when stressed.

The study we’ll discuss shows that both instances generally happen. Suppression of appetite leads to a lower amount of meals consumed during the day, as well as an aversion to healthy foods, but also significant overconsumption of hyper-palatable ultra-processed food later on in the day. This eating pattern in itself is a good proxy for viewing how stressed a client is.

Basically, stress generally makes you eat fewer meals overall because of reduced appetite, but that is followed by a major drive to overeat or binge on hyper-palatable food later on. This results in an overconsumption of calories overall with mostly nutrient-devoid foods.

We do have a study on this — it is an animal study, so please keep that in mind, as it’s essential to understand the difference between animal and human studies. Having human studies that are randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews is ideal, but we can still gain good information from animal studies.

What’s important about this particular animal study is that the HPA axis is conserved and nearly identical in humans. That means that we can carry over some of the principles, even if the study isn’t done on humans. For those unfamiliar, the HPA axis is our hormonal axis that produces the main stress hormone, cortisol.

Research on Stress and Appetite

In this research, mice were divided into groups — one receiving a restraint stress protocol, which is a reliable way to induce stress and increase cortisol levels, and the other group was the control group, so they did not receive any stressors.

The mice then had a condition of hyper-palatable food vs. “normal” food, which included lard and sugar-rich chow versus just regular mouse chow.

The group of mice receiving lard and sugar-enriched food that was subject to stress ended up eating less frequently, but then significantly over-ate these “comfort foods” later on, leading to increased adiposity and fat gain.

Interestingly, the mice that had restraint stress but only had access to standard food ate significantly less than all the other groups, and they had the least amount of body fat by the end of the study, presumably because hyper-palatable food wasn’t available to binge on.

The overall signal we’re seeing here is that if hyper-palatable food isn’t an option, we see a decreased appetite for healthy food and, typically, weight loss as a result.

How Stress Impacts Your Client’s Appetite

Bringing this over to humans: We are rarely, if ever, in a situation where hyper-palatable processed food is out of reach, especially in today’s day and age with Postmates, OrderUp, and Uber Eats.

Since most of your client’s pantries and fridges are stocked with hyper-palatable processed food and what’s not stocked is just a few finger taps away, this is another argument to work with clients to manage stress and find healthy coping mechanisms. A pantry re-engineer is always the best choice, but this isn’t always an option for those living with others.

A house full of hyper-palatable processed food may not be something you see with a more intermediate-advanced client. But if someone’s starting on their transformation journey, this might be a habit for them or potentially an unfavorable tendency that they’re trying to get out of.

HPA Blunting from Comfort Foods

How your client manages stress matters. Some ways result in worse health, while other ways result in better health.

What the researchers found in this study is that consuming comfort food actually blunted the cortisol response and HPA axis, which means eating sugar-lard food lowered cortisol levels.

In other words, the mice legitimately “managed their stress” by eating junk. This effect was not seen by the mice eating regular chow.

Mice managed stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) by eating hyper-palatable food. CRH is the first molecule in the cascade that eventually ends up in cortisol release, so you can think of it as halting stress at the source.

This method is undesirable and results in fat gain and poor health. We don’t want to manage stress by eating hyper-palatable, super calorically-dense food. This is only a temporary solution and it’s a very slippery slope to obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic issues.

Caloric Efficiency in Stress

Something else that surfaced in this study that’s a little less intuitive is that the stressed mice had significantly increased caloric efficiency.

What does that mean? Their bodies were much more stingy with storing calories instead of burning them. This was observed by looking at the amount of weight gained versus the number of calories consumed.

Basically, the mice under restraint stress and eating the hyper-palatable food gained more fat than expected for the calories that they were eating. This finding also probably transfers to humans.

We know that chronic stress in humans, amongst other things, causes changes in the microbiome that cause it to potentially harvest more energy from the food we eat, meaning more calories per gram of food.

Systemic Effects of Stress on Hormones – Appetite, Thyroid, and Beyond

Chronic stress has the potential to impact the thyroid and adrenals, worsen or potentially induce gut issues, and impact the brain by shrinking the hippocampus (executive cognition) and hypertrophying the amygdala (fear and excitement center), making us more reactive to stress.

The next thing to look at would be appetite-related hormones under stress. In this particular study, levels of leptin and insulin were also measured. One of leptin’s main functions is long-term satiety, or feeling satisfied and full from meals. Insulin, besides regulating blood sugar, also acts as a short-term satiety hormone in animals and people who aren’t insulin resistant.

The first finding in this study was elevated insulin, which isn’t counterintuitive or unpredictable. The mice ate more calories and therefore gained body fat, ate more sugar, and were stressed. All three of these can induce insulin resistance by themselves, but the combination makes it happen that much faster.

However, leptin levels were also highly increased in the mice. Usually, this will decrease food intake in an attempt to mitigate further weight gain, but elevated leptin did not stop the mice in this instance, so we can suspect that restraint stress quickly induced some degree of leptin resistance as well via HPA axis activation.

A good rule of thumb is that if we see high levels of a hormone but symptoms of deficiency at the same time, then there’s probably resistance to that hormone.

When you combine insulin resistance and leptin resistance, you get dysregulated appetite with higher cravings and energy crashes, even if chronic stress isn’t part of the equation.

Both of these hormones usually suppress appetite when they’re higher in healthy folks, but in states of leptin and insulin resistance, they lose this particular function. When you add the effects of chronic stress, which can potentially worsen those resistances and then itself cause seeking of hyper-palatable foods, you get the result of someone who’s single-mindedly gunning for the salty-crispy-fatties.

Ghrelin, the primary hormone that stimulates appetite, wasn’t measured in this particular study, but we’ve known for a while that chronic stress increases ghrelin concentrations across the board. Increased ghrelin results in higher baseline fasting ghrelin and ghrelin that doesn’t fall as much in response to eating. In other words, you’re hungrier when you’re not eating, and you also don’t get as much of a satiety response when you do eat.

How Stress Impacts Weight Gain

Chronic stress facilitates fat gain and poor health in several ways and the appetite effects are just one part of that. This should be differentiated from acute stress that goes away, such as exercise. When stress is acute, it almost always lowers appetite, but when it’s chronic, it may have the effect of temporarily under-eating and then consuming hyper-palatable food later on, something I’ve repeatedly seen with clients.

There might be some situations where strength training will lead to a bit more appetite later in the day. Some people out-exercise the caloric threshold they’re trying to adhere to, and we see that, for them, exercise is such a potent stimulator of appetite that they need to manage that.

There are also people who don’t eat most of the day but then tend to overeat at dinner and go really hard in the paint on those evening snacks while watching TV. They may not necessarily describe it to you like that in their check-in, but that’s a general sentiment. Maybe they’re fasting a little bit or going low calorie, making healthier choices while they’re training and maybe they don’t have a ton of appetite right after that, but then they’re potentially overeating later on.

Managing Clients’ Stress

If your client is a high-stress individual, it’s imperative that you help them manage it. There are many ways to aid your clients, but the gist of what we as fitness coaches are trying to accomplish is getting the client out of rumination mode — the place where they’re worried about deadlines and what’s to come or maybe that stupid thing they said to their boss 3 weeks ago.

We have a podcast on this, episode 224: Stress Management Principles. This is a deep dive into all the potential management practices and their effects. Everything from breathwork, meditation, and walks in nature, to creative therapies like art, music, etc. All those have a good effect on bringing down stress levels if you’re unclear on exactly how to manage your or your client’s stress.

Stress impacts appetite in various ways for clients. Even if there’s potentially an acute period of undereating, they may overconsume hyper-palatable foods later on, which can be detrimental to their fitness transformation.

Chronic and acute stress have different impacts both on HPA axis function and on appetite and food choice. So be sure to differentiate between the two; don’t be afraid of a little healthy acute stress, like exercise. This could also be the difference between having a stressful day once in a while and having a long-term stressor or something that’s going on repeatedly in the client’s life.

Recap and Summary

It’s important to remember to communicate with your clients and understand what they’re going through, the food choices they are making when they’re under stress, their appetite, biofeedback, and the food that’s available to them.

Some of these values can be tested in serum labs, and to make the best choices for our clients, we have to understand the connection between serum labs, biofeedback, their nutritional choices, and food journaling. All of these things go hand in hand to take a comprehensive 360 view of the client’s case, which is what we’re always trying to do with Functional Nutrition and Metabolism School.

Hopefully, this study brought some attention to the topic of appetite and stress, and how a client’s behavior and food choices may change over time.

Some additional human research to pay attention to in this particular case is this study. It examined how individuals’ levels of cortisol, ghrelin, stress, and other factors predicted their weight changes over the following 6 months.

The bottom line here is that stress will affect your client’s appetite in some way. If managing stress isn’t already one of the main pillars of your coaching business, it should be now.

References

Norman Pecoraro, Faith Reyes, Francisca Gomez, Aditi Bhargava, Mary F. Dallman, Chronic Stress Promotes Palatable Feeding, which Reduces Signs of Stress: Feedforward and Feedback Effects of Chronic Stress, Endocrinology, Volume 145, Issue 8, 1 August 2004, Pages 3754–3762, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2004-0305

Chao AM, Jastreboff AM, White MA, Grilo CM, Sinha R. Stress, cortisol, and other appetite-related hormones: Prospective prediction of 6-month changes in food cravings and weight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017 Apr;25(4):713-720. doi: 10.1002/oby.21790. PMID: 28349668; PMCID: PMC5373497.